5 rules for open source maintenance

Guidelines for publishing and maintaining open source projects.

Thanks to continuing innovation of software development tools and services, it has never been easier to start a software project and publish it under an open license. While this has lead to the availability of a huge arsenal of open source software projects, the number of qualitative projects that are worth reusing is of a significantly smaller order of magnitude. Based on personal experience, I provide five guidelines in this post that will help you to publish and maintain highly qualitative open-source software.

While the task of programming is a key aspect for (open source) software projects, it is certainly not the only important aspect. In this post, I’m not going to focus on programming techniques (for which other great blogs exists). Instead, this post contains guidelines for the tasks and mindset that accompany open source software development.

While this post contains several examples using specific tools, services, and programming languages, these guidelines are independent of those, and can be applied to most environment involving open source software development.

1. Have a clear goal in mind, and stick to it

“Do not try to do everything. Do one thing well.” – Steve Jobs

Good software projects typically solve a very specific problem within a certain niche. When starting a new project, it is therefore important to have a clear view on the problem, and a vision of how you aim to solve it.

A popular vision within the JavaScript community involves creating small, dedicated packages.

Such a JavaScript package thereby contains only very few lines of code, and does a very specific thing.

Any details surrounding the implementation of this specific thing can thereby by hidden away behind a package name,

such as rimraf (rm -rf for Node.js),

which can then usually be invoked in a straightforward manner.

This vision resulted in npm becoming the largest package manager in the world,

as it contains packages for nearly any functionality imaginable.

A major advantage of small, dedicated software packages, is that this makes testing easy. While a large package with many features can lead to a combinatorial explosion in the amount of ways it can be used, small packages can only be used in a very select number of ways. Therefore, small packages require fewer tests to cover its full range of functionality.

A potential danger for established projects is that they can deviate from their initial goal, and start solving problems that are too distinct from the original problem. This danger can present itself due to the development excitement of maintainers of the project, or by externals that are requesting features that are only slightly related to the project. In these cases, it is the responsibility of the maintainers to strictly define the bounds of the project scope. One good approach for strictly defining such a scope is by creating a document stating the goal of the project, and explaining the problem it aims to solve.

Rejecting new features from maintainers or external can often lead to disappointment or even anger. By making a document explaining the project’s goal public, the blame of such a rejection can be placed on this document, which often reduces any anger towards the messenger of this rejection.

2. Free up your valuable time through automation

The division of effort that goes into a software project often follows the Pareto principle, whereby most of the effort goes into final part of the software lifecycle, i.e., its maintenance. Proper software maintenance involves tasks such as issue management, avoiding regressions, maintaining code quality, and modernising the codebase. Such tasks may require a lot of manual effort for a maintainer, which are often composed of similar, repeatable, and dull tasks. Therefore, it is highly recommended to automate these tasks as much as possible, and thereby cut away any unnecessary noise, so that you can focus on the things you really want to do. Hereafter, I will give some concrete examples on what tasks may be automated.

Issue management

Open-source projects usually allow people to open issues for reporting bugs, requesting new features, or asking general questions. The creation of such an issue typically initiates a discussion between a maintainer and the issue creator. In practise, many of these discussions follow a similar workflow, where a maintainer has to ask the same kinds of questions for each new issue. For example, for bug reports, a maintainer may have to consistently ask for the software version, a crashlog, and steps to reproduce the problem.

If a certain type of issue follows a common format, then creating issue templates may lower the required effort per issue. Such a template may for example provide required fields for providing the software version, a crashlog, and steps to reproduce the problem. Most popular issue management services provide such an issue template functionality, such as GitHub.

One could go even a step further, and automate the triaging of issues based on these templates. For instance, I often make use of the project board functionality on GitHub to categorize and prioritize my issues. Through automation tools such as GitHub actions, new issues can be added to project boards, and categorized and prioritized based on their contents.

Finally, keeping track of stale issues can also be tricky.

For instance, a maintainer may ask the issue creator for additional details surrounding a bug,

but the issue creator may never reply for whatever reason.

Such issues may pollute the issue board of maintainers,

and are therefore better closed if no reply is given for a certain period of time.

Such tasks may also require a lot of manual effort,

and are better left for machines to automate.

For example, after a maintainer has assigned a specific issue label (such as more-information-needed),

a cron job may regularly check all open issues with this label,

and close them if they have received no reply after a certain period of time.

Regression avoidance and maintaining code quality

A set of (unit, integration, system, …) tests with a full coverage of the code is crucial for achieving stable software projects. In order to check that existing functionality does not break after making changes, these tests must be executed regularly. Furthermore, in order to ensure that your code is well-readable, and meets the accepted code standards of this project, there is a need for a set of linter rules, which must also be executed regularly by linting software.

Invoking tests and linters manually can end up requiring a lot of manual effort. This is why continuous integration (CI) tools have become popular, as they can invoke these regularly, or upon each new commit. For open-source projects, CI tools such as Azure Pipelines and GitHub actions are often free to use.

Modernising codebase

Quickly evolving programming environments such as JavaScript typically go hand in hand with regular updates within the dependencies of your software projects. These updates may be done to introduce new features, optimize existing features, fix bugs, or solve security vulnerabilities. As such, it is considered a good practise to update dependencies of a software project as soon as possible, so that your project and its users can quickly make use of these enhancements.

For projects with many dependencies, updating them can require a lot of manual effort, some of which may again be automatable. Services such as Renovate and Dependabot are free for open-source projects, and can be configured to scan your dependencies, track updates, and send pull requests for updating them. Together with a well-configured CI setup with a good test coverage, these tools will quickly show you what dependencies can be updated safely, and which ones break the code and will require changes.

3. Document for others, and yourself

Most developers will tell you that they don’t like writing documentation, and that they are bad at it. At the same time, most developers expect that the software they make use of is easy to understand without having to dive into its source code. Therefore, most developers understand the need for documentation, and simply have to accept that a good software project must have it.

I have experienced two major motivations for writing good documentation. First, you have to take into account your future-self. If you write a software library, and want to extend it or fix something with it a couple of years later, chances are big that you forgot how it worked, and perhaps even how to use it. Time-wise, it is more efficient to write out the important details about this software while you still have everything clear in your mind, compared to re-learning how everything works a couple of years layer. Second, if you don’t like explaining things to people, then make sure you only have to do it once. If you have a good software project, people will flock to it, and start asking questions about it. If your project only has minimal to no documentation, then people will certainly ask questions about more advanced usage, and the same questions will probably re-occur. Instead of having to reply to the same questions over and over again, it is more time-efficient to document it well once, and point people to this documentation so that there will not even be a need for questions.

There is also the question as to what needs to be documented, for which your future-self may again be helpful. Obviously, instructions on how to install and usage the tool are crucial for any documentation, but you should probably go a bit further. If you want your future-self or others be able to work on the project in the future, you will need to somehow document its main architectural decisions in some kind of contribution guide, and non-trivial parts of the source code. This contribution guide should also contain details surrounding the management of this project, such as the CI setup, issue management, the release process, and so on.

4. Take into account software dynamics

Medium to large-scale software libraries that change often over time, will have to determine a strategy on how to handle such changes. This is because dependents of such libraries depend on a certain level of stability across different releases, as it is not feasible for dependents to modify their source code every time there is an update to such a library.

A good approach for software libraries, is to make use of semantic versioning, which allows dependents (and automation tools) to easily see what kind of update a new release involves. A major change involves breaking changes to the library, which may require dependents to change their source code when updating to this release. Therefore, these types of changes are the most expensive kind, and should be avoided until absolutely necessary. A good practise for software libraries is to limit breaking changes, and to make necessary changes backwards-compatible.

Obviously, software libraries with a long version history are mostly not able to remain backwards-compatible ad infinitum, because accumulating backwards-compatibility can become increasingly expensive to maintain. In such cases, a breaking change may be warranted, which will lead to a major version increment. It may however be good to accumulate breaking changes to major version increments that don’t occur too often. This is to alleviate the expensive effort from dependents to update to major versions too regularly. For example, the Node.js runtime releases a new major version every six months, and ensures backwards-compatibility for the period inbetween.

5. Make maintenance fun, and have it

Being an open source software maintainer has a very small chance of leading to fame and wealth, so let’s not bother with those. The thing that drives most maintainers, are curiosity and plain fun. Not only are these things important for yourself, it is also crucial for attracting other maintainers for your projects.

While the start of a project is usually a very exciting time, this state always fades away after a while. Instead of counting on strict discipline for ensuring the maintenance of your project, it is important that there are other factors that will drive you to maintain this project. Otherwise your project will not last.

What drives me most in my projects, is simply being able to play around with things. If you are able to see software maintenance as something as like a game, then maintenance can be transformed from a “must” into a “want”, so that you can actually enjoy maintenance. If fun aspects are not clearly present, then there may be a need to change some things in your maintenance process, and these may very well be just small things.

Hack your reward system

What a person likes is just a part of the brain’s reward system. Since neuroscientists know quite a bit about the brain’s mechanisms already, it is possible to hook into these by aligning your software maintenance process with them.

For instance, it is known that colors are tied to emotions, and changes in visual appearance of things can therefore change our mood and mindset. Since the stereotypical software developers stares at white text on black screens, the task of making things visually appealing can therefore be very low-cost and beneficial. For example, adding some colors to spice up your terminal –or some emojis if you really want to get crazy– can really make your time more enjoyable.

Visualization of your progress is also very important to maintain your drive. Therefore, try to make your progress tangible as soon as possible. For example, if you are developing an app with a graphical user userface, make use of live compilation tools to immediately see your code changes applied visually. This will make it much more pleasurable during development, compared to being stuck for hours in your IDE without any tangible outcome.

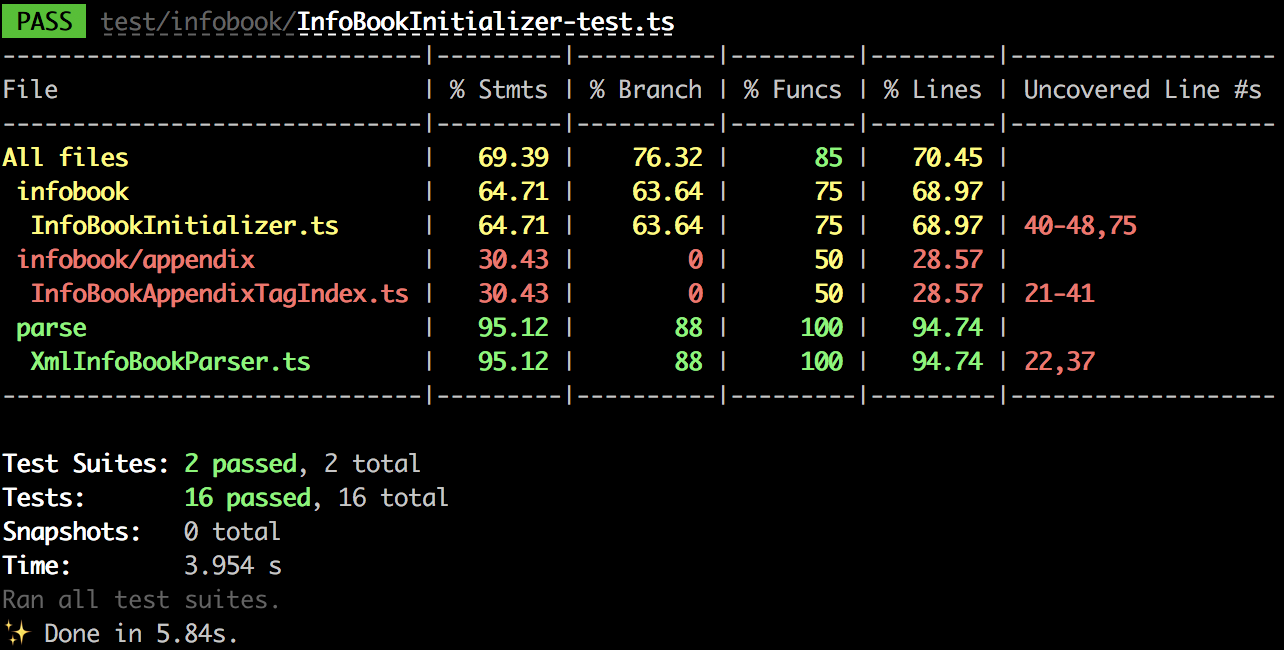

Jest uses colors to draw attention to important parts, and add another dimension for visualizing test coverage. In doing so, it encourages everything to become green for full test coverage.

You could even go a step further, and create dedicated tools for improving the visualization of certain tasks. For example, I once had to handle a long lists of failures of a test suite. In order to make this annoying task fun, I developed a tool to quickly run these tests, and report on them in a visually pleasing manner.

Reciprocal kindness

Open source maintainers are often annoyed by the large frequency of impoliteness among people that report issues. While this often leads to hostility and conflict, or even reporters getting blocked, I learned that such an approach is usually counterproductive. Most people that want to do the effort of reporting an issue really want to make things better, in a way they think is good.

Therefore, it is usually a good strategy to assume good intentions from issue reporters, even if the writing style of the issue may not necessarily reflect this. Make sure that you always reply in a kind manner, which may lead to a kind response. And who knows, if done well, it may even lead to a new contributor for your project (I’ve had it happen before!).

Summary

To sum all of this up,

- Have a clear goal in mind, and stick to it

- Free up your valuable time through automation

- Document for others, and yourself

- Take into account software dynamics

- Make maintenance fun, and have it

Note that the guidelines in this post are based on my personal experience. Surely, there are many other important aspects to open source software development and maintenance. So if you have any other valuable insights into these topics, or if you have other views on these guidelines (especially conflicting ones!), please share them as a comment, so we can commonly learn more.